Sarah Lucas's Bunnies and the Radicalisation of Cloth

- Claudia Stanley

- Feb 9, 2024

- 5 min read

Installation view, Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas, Tate Britain, 28 September 2023 – 14 January 2024

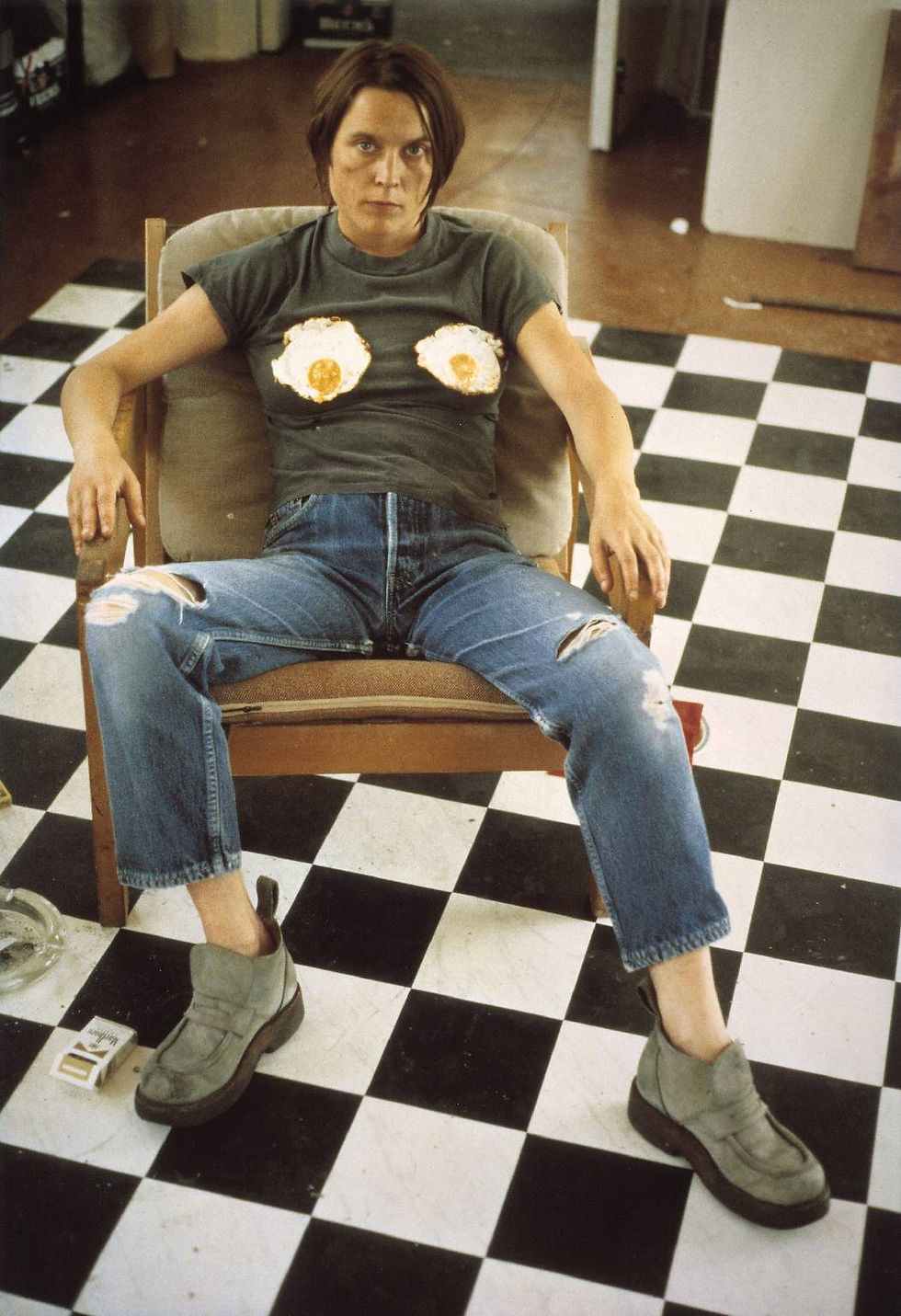

The communicative power of clothing is well documented throughout Sarah Lucas’s artistic practice. In her 1996 Self Portrait with Fried Eggs, Lucas is the pinnacle of cool androgyny. She wears stereotypically masculine garments (crew-neck t-shirts and brothel creepers both have military origins), dominating the frame unapologetically. Her confidence is overpowering. With her spread legs and an unfaltering, commanding gaze, Lucas tries masculinity on for size, wearing it like a uniform. This is all perfectly undermined by two fried eggs on her chest which act as substitutes for breasts, simultaneously concealing and highlighting the female form that sits beneath her masculine exterior. It’s silly, sexy and subversive.

Sarah Lucas, Self Portrait with Fried Eggs, 1996, Tate, © Sarah Lucas

Lucas’s dressed body is not the only platform on which she employs clothing to unravel archaic notions of gender. Her sculptural series of Bunny Girls radicalises cloth to challenge expectations of the female body and to undermine the art historical canon of the female nude. Made from stuffed nylon tights, Lucas’s bunnies are hybrids of flesh and fabric. She fills and contorts tights to take on the appearance of predominantly headless female figures with disconcerting proportions and impossible flexibility. Tights conjure thoughts of women in states of undress and, by extension, of sex. But once tights are severed from the body, they take on an unappealing quality, like clumps of hair or nail clippings. Throughout her ongoing series of bunnies, Lucas exposes how a mundane garment can be manipulated into something deeply unsettling and disruptive.

Sarah Lucas, Bunny, 1997, Private Collection, © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ

In Tate Britain’s recent exhibition Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas, Lucas’s first ever bunny is one of the primary exhibits you encounter (Bunny, 1997). Slumped on a chair, a pair of stuffed flesh-toned tights take on the uncanny resemblance of legs. The waistband of the tights is pulled over the back of the chair to form a torso. This bunny wears its own pair of black stockings, which further blurs the line between human and hosiery. Empty tights dangle on either side, like limp arms. Another pair of stuffed tights flop over the headless ‘body’, taking on the appearance of fleshy and flaccid bunny ears, breasts, or arms (it’s somewhat anatomically ambiguous). A metal clamp fixes the bunny to the back of the chair, creating a sense of painful entrapment. Its deflated posture conveys vulnerability and powerlessness under the ever-present, over critical male gaze.

Historically, sculptural depictions of the female nude were elevated onto plinths. Lucas parodies this by using an eclectic mix of chairs as podiums for her bunnies. Chairs themselves have been humanised through language - they have arms, legs and backs. The fact that Lucas places her bunnies on chairs further animates them, grounding them within the domestic realm. It calls to mind Allen Jones’ Chair (1969), a piece of furniture which resembles a half-naked woman lying on her back wearing lace-up knee-high boots, latex underwear and gloves (it’s part of a charming set alongside a table and hatstand). Her thighs are bound to her lower back with a thick belt, folding her in half. A pane of glass separated the backs of her thighs from a cushion, and her raised calves become a backrest. Her expression is totally passive, unreadable, and yields no sense of engagement or active enjoyment. But then again, it’s a chair. It’s not supposed to be having a nice time. It’s not a sentient or sexual being. Jones not only binds and entraps the female form within the domestic realm, he reduces women to objects for male comfort, voyeurism, and sexual gratification. Comparatively, Lucas humanises inanimate tights into figures that confront expectations of the sexualised female body and ridicule the male gaze.

Allen Jones, Chair, 1969, Tate, © Allen Jones

Yet there is comedy in Lucas’s work. The second room of Happy Gas is full of bunnies. Each limp, languid, lumpy lady is as humorous and unnerving as her neighbour. Some are slumped, others straddle chairs. Some stubbornly cross their arms over swollen breasts, others fold in on themselves, contorting and entangling their limbs in impossible, yet suggestive, positions. Each bunny is christened with a comical title that parodies pornographic pseudonyms: Honey Pie, Sex Bomb, Cherry, Angel, Slag, Cool Chick Baby, and - the most sultry of them all - Cross Doris. Yet the titles are hardly needed. Each bunny has a unique personality, which is primarily communicated through how they are dressed. For instance, Cool Chick Baby (2020) sits with her knees curled up to her bare chest. She sports platform converse high-top heels and inky blue stockings that stretch over unnaturally long legs up to thin thighs. The curved seat of her trendy mid-century chair mirrors her own sinuous form. Cool Chick Baby is not like other girls. She’d definitely recite the ‘cool girl’ monologue from Gone Girl in the smoking area and she takes ‘Knee Socks’ by the Arctic Monkeys a bit too personally. Yet, any pandering to the male gaze is counterbalanced by her boneless arms that snake and weave around her body in a nightmarish tangle of flesh.

Sarah Lucas, Cool Chick Baby, 2020, Collection of Alexander V. Petalas © Sarah Lucas. Courtesy Sadie Coles HQ. Photo: Robert Glowacki

Never to be confined to one medium, Lucas moves away from fabric and into less

ephemeral materials. The affectionately named Slag (2022) is identical in texture to all the

bunnies made from nylon tights. Seams and wrinkles are visible along her arms and legs, and her deflated posture creates the impression of weightlessly sliding off her chair. Her

stomach rolls look tantalisingly tactile. But on realising that Slag is made of concrete, an

entirely new interpretation of this bunny and the female body is formed. Perhaps Lucas is

communicating that the female form, despite its perceived softness and malleability, is an

indestructible force.

Lucas takes this idea of inner strength further with her Goddess sculpture (2022). Made of

bronze, concrete and steel, Goddess is the most animated of all the bunnies. She perches

on the back of a chair, as if rising up out of her calculated state of repose. Her arms are

outstretched, instead of limp in her lap or protectively wrapped around her body. The

openness and shamelessness of her body oscillates out to the viewer, as if she is

reaching to embrace those criticising her through their gaze. Her inner steeliness radiates

out through her iridescent bronze skin, marking a sharp contrast to the almost translucent

appearance of the nylon bunnies.

Lucas’s sense of playfulness transcends materials and mediums. She disrupts the

archetype of patriarchal, art historical female nudes. She weaponises clothing to make

powerful, positive statements about female sexuality and bodily diversity. It is not the

limp, boneless, lifeless forms that make an audience with Lucas’s bunnies so

uncomfortable, and yet so compelling. Perhaps it is cloth itself. Is it the physical proximity

to (and the disembodied resemblance of) human skin that instils flesh-toned tights with

their fetishistic weirdness? Lucas uses the universal language of clothing to dismantle

archaic notions of femininity and corporeality, while exposing the humour and humanity in

the uncanny and unnerving.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

Claudia Stanley is an MA graduate from the Courtauld Institute of Art, specialising in Dress History. She has written for The Courtauld’s Documenting Fashion: A Dress History Blog, and The Courtauld’s peer-reviewed journal Immediations. Did she mention she went to The Courtauld?

Loved this, Claudia!

Great to read your writing and perspective. I have to say I was never really a fan of Lucas and a big part of me really wishes that she'd moved on some from her early stuff, witty as it was. I really wanted to like this show, and there were bits that I did, like the huge wallpaper portrait images of Lucas herself. However, despite how great it also was to see all the bunnies together as they were, to be able to compare/contrast the different media, textures, colours, footwear etc., it left me wanting. I'd love to read your critique of Women in Revolt.